Freshly shorn sheep on a farm in Slovakia, 2023. Image credit: Zuzana Mit / We Animals Media

For many, the thought of wool production conjures comforting scenes of countryside idylls with sheep dotted on the landscape, grazing peacefully. And indeed, recent years have seen a surge in the wool industry’s marketing efforts to position it as the ultimate natural material, superior to its synthetic counterparts. Whilst the harmful effects of animal agriculture as a food production system have at last received overdue scrutiny in mainstream climate change discourse, animals used for materials are often still left out of the discussion. Wool, with its bucolic reputation and beloved place in our wardrobes, is not exempt from the hard compromises on sustainability and animal welfare that befalls all animal farming, and is neither as sustainable nor as humane as its romanticized image suggests. Here we peel back the layers on wool’s production, and look at the emerging alternatives in next-gen wool.

Note: Wool can come from a wide range of animals, including sheep, alpaca, goats, muskoxen, rabbits, camelids, and more, with the most popular animal for wool being sheep, which is the focus of this blog post.

By-product or co-product?

It is still not widely understood that animal materials like wool and leather are not waste-saving byproducts but in fact ‘co-products’ of the meat industry. Thinking of them as byproducts is misleading and simplistic, obfuscating the interdependent and thin profit margined reality of animal agriculture’s economics, where even the small profits contributed by hides and wool play an important role in supporting the whole business. It also distracts from the fact that animal-based materials like wool are not “vegetarian” products – they enable an industry of animal slaughter.

“Wool and leather are not byproducts of meat production, they’re co-products: producers support their livestock operations by selling meat as well as wool and hides, all of which keeps them afloat,” Matthew Hayek, an assistant professor of environmental studies at New York University, told Vox.

A ewe and a newborn lamb at a regional sheep farm in Poland. The males are sent to slaughter for meat at a young age, while the females are reared for the production of wool. Poland, 2019. Andrew Skowron / We Animals Media

Therefore, farming sheep for wool is not financially viable without also killing them for meat. This harsh truth became clear to Nicole Rawling, MII’s CEO, when she was invited by a household-name apparel brand to visit a wool farm in California a few years ago. The farm was purportedly the gold standard for ecologically sustainable and humane wool production. When asked directly if they kill any of the sheep in their business model, the farmers conceded that, yes, every year they breed sheep and kill half of the lambs (mostly males) for meat to maintain sufficient profits.

Being a regeneratively-focused operation, the farm also had a carbon-sequestering program. They divulged that the sequestration was not occurring through any process of how the sheep were reared on the land, but instead from the farm buying in local compost, which they spread on their fields. Sometimes the sheep helped to integrate it into the soil with their hooves, but this was not requisite. What’s more, the compost largely came from local dairy farms, meaning it supported animal agriculture further.

Young lambs several days after birth at a regional sheep farm in Poland. The animals are slaughtered for meat at a young age or are reared for the production of wool. Poland, 2019. Andrew Skowron / We Animals Media

It should also be noted that to obtain shearling (the pelt of the sheep with skin and wool still attached) sheep and lambs must be killed.

Wool has high environmental impacts

A single, clear assessment of the environmental impact of wool is very difficult to find or produce, given the huge diversity in regards to different production systems and a widespread lack of data for various stages of the supply chain. Additionally, with the co-production of meat and wool it is hard to separate and analyze the impact of wool alone, as many farms vary in their breakdown of products.

Emissions

Ruminants like sheep produce vast amounts of methane, the potent greenhouse gas that has 86 times the impact of carbon dioxide over a 20 year period, and which is responsible for about a quarter of all global warming. Animal agriculture produces 16.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Feed production and land conversion for grazing contribute to that, but nearly half of the sector’s emissions stem from methane itself. Ruminants produce 90% of that.

1 kg of wool equates to driving for between 22-100 miles

As discussed, GHG emissions vary between production systems, but even at the lower end, they are considerably higher than synthetic or plant fibers’ emissions. In Australia, the world’s biggest wool producer, the CO2 equivalent for 1 kg of raw wool ranges between 8.9kg and 30.6kg. In the U.S., it could be as high as 41kg CO2e. Therefore, at the lower end, 1 kg of wool can be compared to driving for 22 miles, and at the high end, 100 miles. These emissions are only for raw wool, they do not include wool processing, meat production or other co-products, so the actual impact is likely much higher. And only 68% of greasy wool becomes usable fiber after scouring (the process of cleaning).

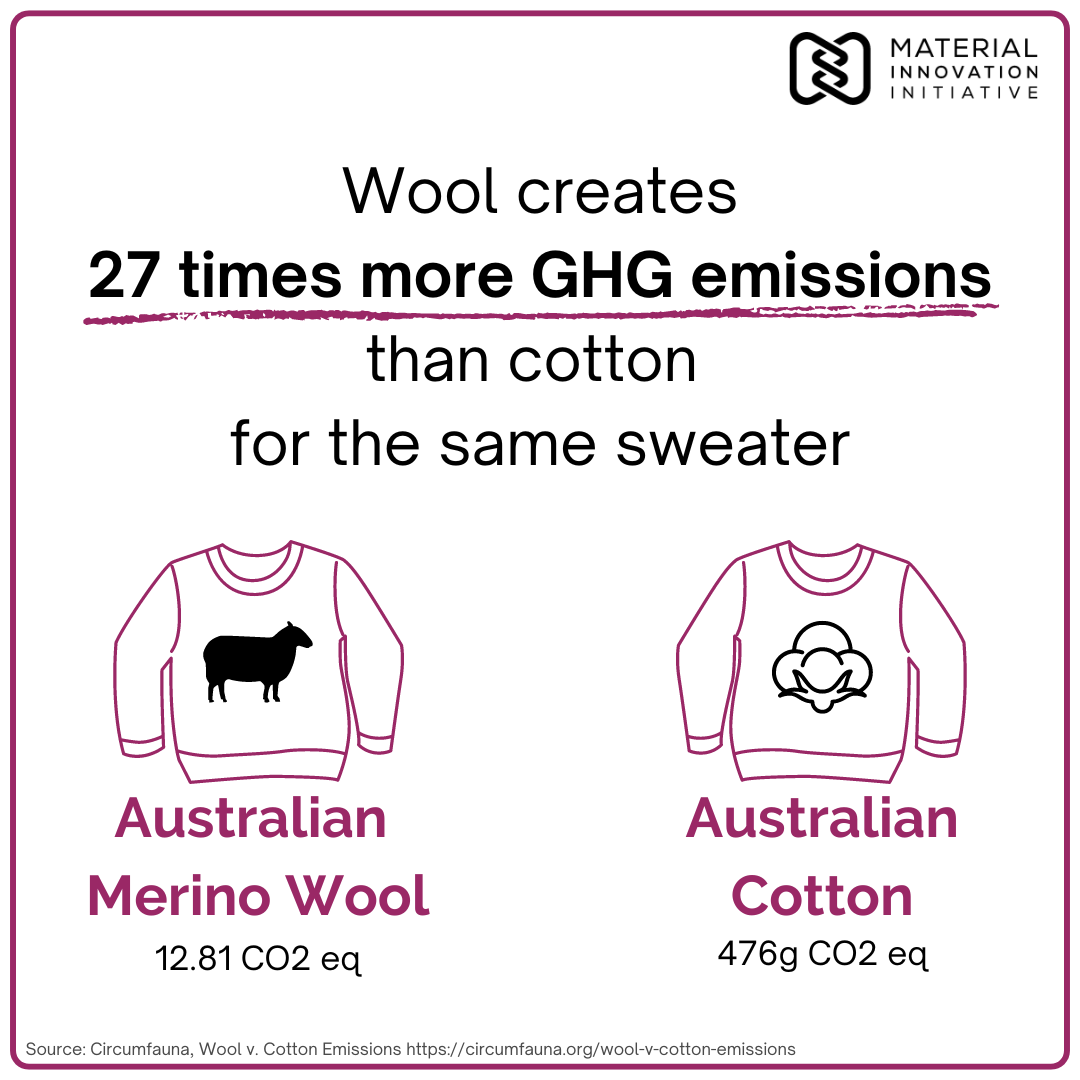

To put this in the context of alternative fibers, one Australian merino wool sweater is responsible for 27 times more GHG emissions than an Australian cotton one, the wool version equals 12.81kg CO2e, the cotton one 476g CO2e.

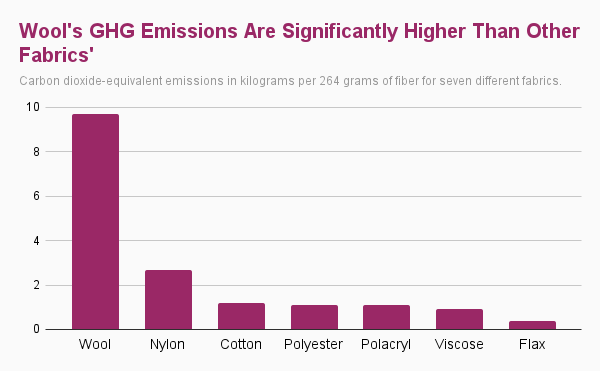

One study by Ecoinvent, a Swiss sustainability assessment nonprofit, found that wool has much higher greenhouse gas emissions than other fabrics, including nearly nine times as much as polyester.

One study’s estimate of greenhouse gas emissions per 264g of fiber for seven different fabrics. Study by Ecoinvent, original graph created by Vox.

One study’s estimate of greenhouse gas emissions per 264g of fiber for seven different fabrics. Study by Ecoinvent, original graph created by Vox.

More research is needed to examine the during-life energy use and impacts of different fibers.

Resource use

Land

Wool is a land intensive fiber. In Australia, wool production occupies 20% of agricultural land. And yet, compared to cotton, it is substantially less productive. It takes 44.04 hectares of land to produce one bale of Australian wool, but only 0.12 hectares for Australian cotton, meaning it requires 467 times more land than cotton; the figure drops even further for viscose and lyocell.

Sheep farming’s impact on land occupation is debated. While some argue that grazing on steppe grasslands can be sustainable with good management and makes use of otherwise non-farmable land, cases like the Karoo in South Africa give evidence to the contrary, where high stock numbers have led to severe soil erosion, desertification and the formation of badlands due to changes in vegetation. Argentina’s steep decline in wool production is attributed to similar issues. Cases in Australia and Patagonia where sheep have been removed and land improvements recorded are notable here.

Water

Water use is also high for wool production. Large amounts are required for the on-farm phase, whether for production of nitrogenous fertilizers typically required in fine wool farms in higher rainfall areas or for the sheep’s drinking water in dryer environments, and also in scouring and dyeing of wool fibers.

Chemicals and their effects

Scouring also requires large volumes of chemical-heavy detergents, such as sulfuric acid, and water, to remove the grease and debris from raw wool. Even industry bodies report that “wool scouring produces a highly polluting effluent stream which is very difficult to degrade by biological microorganisms.” The organic effluent from a single wool scouring facility is equal to the sewage from a town of 30,000 people.

Freshly shorn wool at a farm in Slovakia, 2023. Image credit: Zuzana Mit / We Animals Media

Biological waste in the form of fecal matter and sheep dip (toxic chemicals used to reduce parasites on sheep) present further problems, contaminating waterways and soil near farms, and posing significant health threats for a variety of animals including humans.

A threat to biodiversity

Habitat loss through deforestation and land degradation is the greatest threat to biodiversity, and animal agriculture is the leading cause of habitat loss. So even in cases where better practices are in place such as regenerative wool farming, sheep are still a threat to native wildlife and ecosystems. In many areas farmers are allowed to kill wild animals such as kangaroos and coyotes that are considered “pests”.

Furthermore, a 2021 report by the Center for Biodiversity and Collective Fashion Justice states on the topic of regenerative wool that “there is no evidence that carbon sequestration can be successful across diverse geographic ranges at current industry scale, or that it can fully offset the emissions created by the animals and the production of animal-based products.” The vast areas of land required by ruminants could be used instead for more effective native carbon sequestering ecosystems.

Animal welfare issues are common in the wool industry

Being shorn is not just a benign haircut for sheep, it is a cause for ethical concern. Workers often get paid by volume, not the hour, causing them to work quickly and deprioritize the sheeps’ welfare. Plenty of times, this process has been documented to be distressing and brutal for the sheep, being subjected not only to cuts from the shears, but also violent behavior from workers such as kicking, punching, shouting, and stitching up wounds without pain relief.

A sheep on a dairy farm undergoes shearing with electric trimmers. A trained shearer has flipped them over and restrained them by their neck to complete this twice-yearly procedure. Slovakia, 2023. Image credit: Zuzana Mit / We Animals Media

Lamb mortality is high in the wool industry, ranging from 9-20%, but it’s especially high in Australia – the world’s biggest wool producer with 70 million sheep. 10-15 million lambs die within 48 hours of birth every year there due to harsh conditions. Mortality rates are between 20-30% and sometimes even as astoundingly high as 70%. The reason for these deaths stems from economic interests. Despite sheep naturally tending to give birth in spring, winter lambing is more cost-effective as lambs can be fattened on grass after weaning, saving money spent on feed.

But it’s not just the lambs who die, their mothers, the ewes, do too, often due to the bodily strain from selective breeding that means twin, triplet and quadruplet births are commonplace, when sheep would naturally tend to give birth to a single baby, like humans. Prolapses are therefore common and frequently result in death.

Sheep can live up to 12 years old, but most live to just half of that in the wool industry. And many lambs are killed at 6 months old for their meat and skin. Hair (wool) quality declines with age.

The practice of mulesing, or live lamb cutting, is one of the biggest welfare issues in wool production. Sheep are susceptible to flystrike – a painful infestation of flies that have laid their eggs in the folds of skin around a sheep’s buttocks (excess folds of skin stem from selective breeding to maximize hair follicles and therefore wool). To prevent flystrike, lambs have skin cut away from their rears often with inadequate or no pain relief, the pain can last for days and the wound takes weeks to heal. Lambs may die from this too. A growing number of brands have adopted or are pledging to adopt certified systems that avoid the practice, which can even provide financial benefits for wool producers. Despite this, 70% of Australian lambs are still subjected to this mutilation.

Flies invade a disinfected wound on the body of a freshly shorn sheep in Slovakia, 2023. Image credit: Zuzana Mit / We Animals Media

Cashmere (goat) and alpaca wool are smaller industries than sheep’s but no less severe in environmental impact and animal cruelty.

Naturalistic fallacies of wool production

Sheep have not simply evolved to produce such hefty quantities of hair for us, but have been deliberately and selectively bred that way, to maximize productivity. Domesticated sheep are descendents of the wild mouflon, who naturally thermo-regulate themselves by shedding their hair with the seasons. Sheep do not do this and we have made them dependent on being shorn to survive.

Wool as we know it is a designed product, requiring multiple stages, interventions and processing to be turned into usable fiber. Even if it is not a fiber that is synthesized in a laboratory, just because it has “natural” elements to it, doesn’t necessarily mean it is ethical. To believe what is natural is by default ethical is called a naturalistic fallacy and this mindset is rife towards animal products, something that is highly exploited in animal agribusiness’ marketing.

Sheep are not native to the landscapes in which they are most frequently reared. Their hard hooves erode the soil and they notoriously eat plants almost indiscriminately. Far from being the picture of naturalness we want them to be, they are an unapparent threat to native wildlife and ecosystems (see the section on biodiversity above).

Synthetics aren’t perfect, but they’re lower-impact

Many alternatives to wool come in the form of petroleum-based synthetic fibers, such as acrylic. Microplastic pollution is a serious issue that harms all forms of animals, so synthetic fibers are far from ideal, and yet they rank lower than wool consistently in GHG emissions (see chart above), land and resource use.

But siding with either wool or synthetics is in fact a false dichotomy – there are plant-based alternatives currently available and there’s a third category that is set to replace incumbent animal wool and fully encapsulate its varied and unique characteristics: next-gen wool. Some next-gen materials are not yet 100% biobased, meaning they do currently include petroleum-based plastics, but this is a necessary step in the innovation process towards fully petroleum-free materials. New innovations are often highly scrutinized and criticized for not yet being perfectly sustainable, but innovations require time and patience to reach their full potential. At MII we advocate for progress not perfection.

Moreover, wool and other animal-based materials are not necessarily free from petroleum-derived plastics, either. Wool is frequently blended or dyed with synthetic components anyway, rendering it non-biodegradable. Many brands use wool and synthetic blends to cut costs or enhance machine washability and performance characteristics.

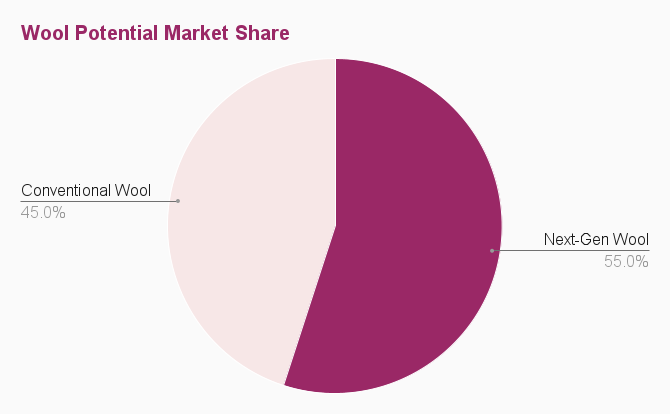

Next-gen wool is the emerging solution

Next-gen wool is the solution being developed by innovators now. It bypasses animal cruelty, is free from harmful microplastics (or aims to be), and is often designed from its inception to be highly sustainable. Our research has shown that the potential market share for next-gen wool is 55% (assuming a future in which next-gen options are widely available, of 73% who indicated they would buy wool products, 55% said they would choose next-gen over conventional wool). In the U.S. 92% of survey participants stated they were at least somewhat open to purchasing next-gen materials including 51% who were somewhat/moderately likely to purchase and 41% who were very/extremely likely to purchase. These are high numbers for consumer openness to new technologies.

Image credit: United Arrows x Spiber

The textile and apparel demand for wool is high, and these applications require a finer wool grade, therefore, innovators would do well to focus on creating alternatives that are comparable to finer wools, in order to tap into the markets with the highest demand. You can discover the innovators working on biomimicry of wool listed in our freely available innovators database. Some of these innovators have collaborated with brands such as Stella McCartney and Goldwin.

To learn more about partnerships between brands and next-gen material innovators, check out our reports here. Sign up to our newsletter here to be notified when our 2024 monthly ‘lookbooks’ drop, these are convenient roundups of the month’s collaborations.

All hats made for vegan actor Joaquin Phoenix in Ridley Scott’s Napoleon were made by Bark Tex, mimicking the wool-felt originals. Image credit: Aidan Monaghan/Apple Original and Columbia Pictures

Learn more about the state of the next-gen materials industry as it currently stands in our recent State of the Industry 2023 Report.